Clinicians often use combination cancer therapies to overcome treatment resistance, and one of the newest options for certain patients with multiple myeloma is isatuximab, a monoclonal antibody (mAb). Approved for use in combination with pomalidomide plus dexamethasone to treat adults with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma who have received at least two prior therapies, isatuximab prolonged progression-free survival by nearly six months and produced an overall response rate of more than 60% in the drug’s clinical trials.

Because isatuximab is a new agent, oncology nurses have little published guidance to refer to when administering and caring for patients receiving the treatment. In their article in the December 2021 issue of the Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, Wilmoth et al. gave an overview of all aspects of isatuximab administration and patient management based on data from its phase III clinical trials.

Isatuximab for Multiple Myeloma

As an anti-CD38 mAb, isatuximab targets a specific epitope on CD38, triggers cell death via multiple mechanisms, inhibits CD38 enzymatic activity, activates antitumor responses, and initiates autologous T-cell responses, Wilmoth et al. said. They explained that it binds to a different isotope than daratumumab, another anti-CD38 mAb, and specifically noted that “isatuximab induces direct apoptosis without crosslinking agents whereas daratumumab uses Fc receptor–mediated crosslinking.”

CD38 is also present in red blood cells (RBCs), so isatuximab’s mechanism of action may temporarily change patients’ allo-antibody lab values and affect the accuracy of analysis for blood transfusions. Patients should get accurate blood type, antibody, and RBC phenotyping before beginning treatment, Wilmoth et al. said.

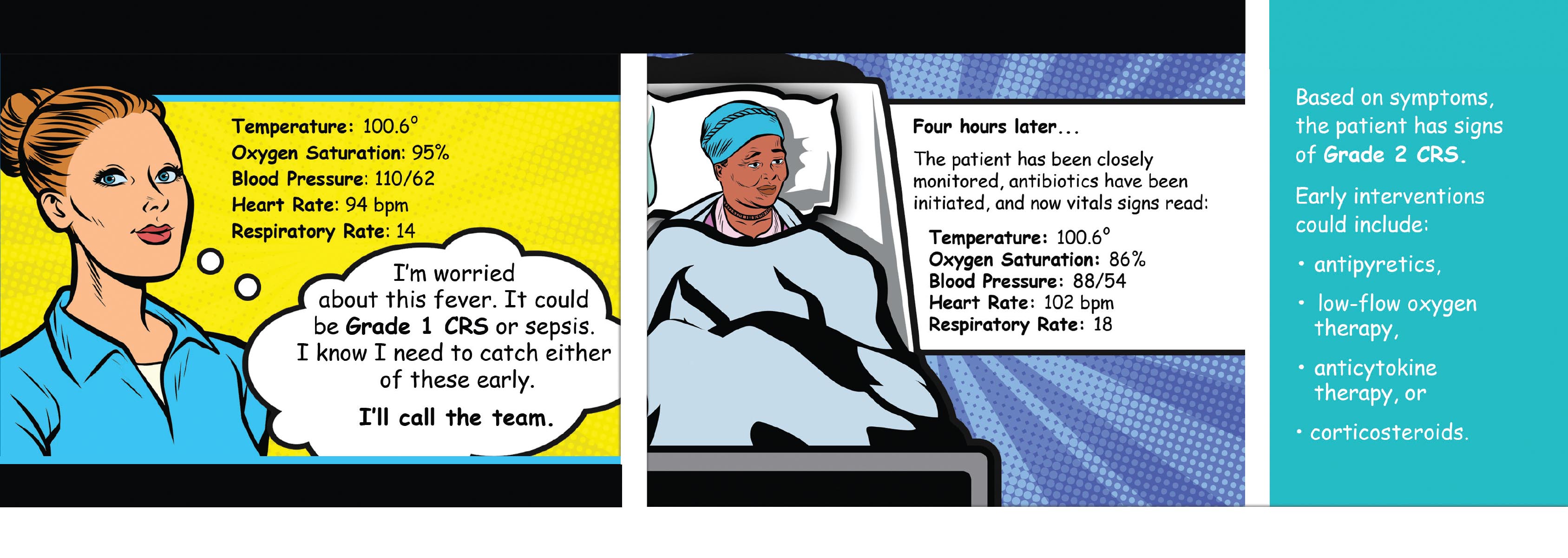

Like other mAbs, isatuximab was generally well tolerated in the clinical trials, but mAbs are associated with immune-mediated infusion reactions; side effects such as flu-like symptoms (e.g., fever, chills, body ache, muscular pain); and serious adverse events (AEs) such as cytokine release syndrome (i.e., a severe, life-threatening emergency with risk to major organ systems).

Wilmoth et al. recommended that oncology nurses use established guidelines and strategies to prevent or quickly recognize and manage severe reactions. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s clinical practice guidelines for immune-related adverse events is available online, and ONS has a clinical practice resource that can help you apply it.

Patients should avoid pregnancy and breastfeeding during and for at least five months after treatment.

Isatuximab Administration

Before the first infusion, oncology nurses should manage patient expectations by educating them on the treatment schedule, infusion duration, frequency of lab testing, preparation requirements for transfusions, and adverse event management, Wilmoth et al. said. Additionally, take an updated patient history and make sure patients have obtained their baseline blood screening tests.

The manufacturer recommends the following premedications, given at least 60 minutes before the first infusion and 15–60 minutes before subsequent ones:

- Dexamethasone 40 mg orally or via IV (reduce to 20 mg for patients aged 75 or older)

- Acetaminophen 650–1,000 mg orally

- H2 receptor antagonists (e.g., famotidine, cimetidine, ranitidine)

- Diphenhydramine (or equivalent cetirizine, promethazine, or dexchlorpheniramine) 25–50 mg, preferably via IV for at least the first four infusions, then either orally or via IV thereafter

The recommended isatuximab dose is weight based at 10 mg/kg, which is administered weekly during the first 28-day cycle, then every other week, along with pomalidomide (4 mg orally on days 1–21 of each cycle) and dexamethasone (40 mg [20 mg for patients aged 75 or older] orally or by IV weekly).

Isatuximab Adverse Events

Wilmoth et al. reported that the most common AEs in isatuximab’s clinical trials were neutropenia (96%), infusion reactions (38%), upper respiratory tract infection (28%), diarrhea (26%), bronchitis (24%), pneumonia (20%), and nausea (15%). To date, the most frequent serious AEs are pneumonia and febrile neutropenia.

Infusion reactions: Monitor patients throughout the infusion for reactions and check their vital signs every 15 minutes for the first hour. Instruct patients to immediately report any symptoms that could indicate a reaction. In isatuximab’s clinical trials, the most common symptoms of an infusion reaction were dyspnea, cough, nausea, and chills, and the dyspnea and hypertension could be severe. See the sidebar for a management algorithm for isatuximab-related infusion reactions.

Neutropenia: Educate patients about infection prevention practices and to immediately report any fevers higher than 100.4°F and other signs and symptoms of infection, including chills, cough, difficulty swallowing, nasal congestion, postnasal drip, mucositis, dysuria, stomatitis, worsening fatigue, sudden onset of malaise, and shortness of breath, Wilmoth et al. advised.

Most patients develop mild neutropenia with an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of less than 1.5 x 109/l and can be managed conservatively. Severe grade 3 (ANC less than 1 x 109/l) or grade 4 (ANC less than 0.5 x 109/l) neutropenia requires a more aggressive approach.

For grade 3 neutropenia without fever, continue antibiotics until ANC recovers to 0.5 x 109/l and stop vancomycin if cultures do not identify resistant gram-positive organisms. If a fever is present, continue IV antibiotics, consider conducting a computed tomography scan, and consult with an infectious disease specialist. If cultures do not indicate infection, discontinue vancomycin.

Wilmoth et al. concluded that patients receiving isatuximab required coordinated care across the interprofessional team, which oncology nurses can help manage. For more information about the nursing considerations for isatuximab, including a case study demonstrating neutropenia management, refer to their full article in the Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing.