A critical and often overlooked component of germline biomarker testing, cascade testing involves identifying biologic relatives at risk for inheriting a specific known family pathogenic variant after it’s first found in the family and extending the offer for germline biomarker testing to them.

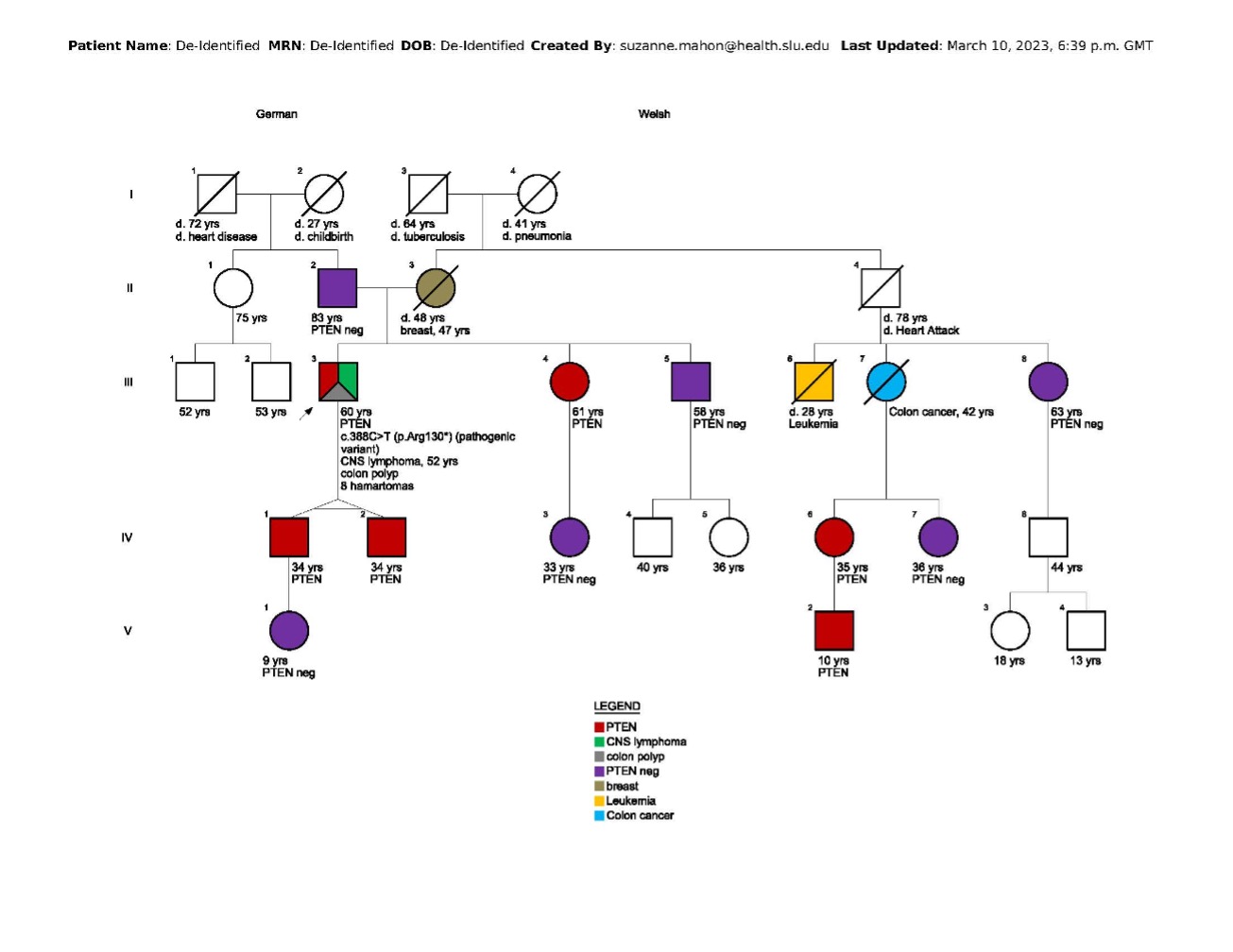

Typically beginning with first-degree relatives (i.e., siblings, parents, and offspring), germline biomarker testing “cascades” through the family depending on who has the pathogenic variant. If a carrier is found, second-degree relatives are notified (i.e., half siblings, aunts, uncles, grandparents, nieces, and nephews), then third-degree relatives (i.e., first cousins). If a family member is not available for testing (i.e., does not want testing or has died), testing moves to more distant family members. Constructing a three-generation pedigree helps genetic professionals identify which family members to test (see sidebar).

What Does the Research Say?

Cascade testing holds great promise and power to identify family members who are asymptomatic and do not know they have a germline pathogenic variant until symptoms develop. By then, they’ve missed the opportunity to follow prevention strategies and their cancer treatments might be less effective. Less than 30% of those who have a relative with an identified germline pathogenic variant undergo cascade testing. Known barriers to cascade testing include cost, insurance constraints, and confidentiality laws.

What Nurses Need to Know

Family members must notify each other that a pathogenic variant has been identified because healthcare providers cannot contact family members. Once notified, healthcare providers can help them understand who should be offered testing and assist coordination with genetic counseling. Family members who live in different geographic regions may need help locating a professional near them. The National Society of Genetic Counselors has a searchable database of genetic counselors by zip code. There may be costs associated with genetic counseling services, but some genetic testing companies offer free cascade testing for family members for a certain amount of time (e.g., 60–180 days) after a pathogenic variant is first identified.

Germline test results are protected under the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA). GINA prohibits health insurance companies and employers from discriminating against an individual based on their genetic information, but it does not protect individuals from discrimination by life, disability, or long-term care insurance companies. Genetic professionals can assist those who need to address any related issues before engaging in cascade testing.

Put Cascade Testing in Action

Oncology nurses can prepare patients for cascade testing counseling using materials such as ONS’s Genetic Counseling and You patient video. The video explains the importance of gathering all family history from both sides and bringing a copy of the relative’s test result to the appointment. Sometimes after reviewing the entire family history, the genetic professional may recommend additional testing.

Talking to their family members about having an increased risk of developing cancer may be difficult for some individuals. Genetic professionals can provide guidance on the best method and timing for those conversations and help the patient anticipate and address family members’ possible reactions. For example, if a family member refuses to talk or consider testing, the patient must respect their decision.

Many genetic professionals offer telehealth services. Telehealth can remove some travel-related barriers, such as time away from work and travel costs, or allow multiple family members to be on a call to receive the information together and support each other. Samples can be collected remotely by shipping a saliva kit to the home and back to the laboratory.

In this family, cascade testing began by clarifying which side of the family carries the pathogenic PTEN variant. The proband’s father tested negative, suggesting maternal transmission. The proband’s sons were both tested, and as expected in identical twins, both carry the pathogenic variant. Because testing is typically offered around age 5 in families with a pathogenic PTEN variant, one twin's (IV 1) 8-year-old daughter was tested and was negative. The proband’s sister tested positive, but her daughter tested negative. The proband’s brother and maternal first cousin (III 8) tested negative, so testing was not indicated for their offspring. The proband’s maternal uncle (II 4) was deceased, as was a maternal cousin (III 7) who died from early-onset colon cancer. One of her two daughters (IV 6) tested positive, as did her grandson (V 2). At that point, all appropriate relatives were offered and completed testing. The cascade testing included 11 family members who now have information that enables them to choose an appropriate plan for cancer prevention and early detection.