By John Hillson, RN, OCN®

Bob is a 68-year-old patient with early-stage cancer of the glottic larynx (right true vocal cord). He is receiving a hypofractionated three-dimensional conformal therapy without concurrent chemotherapy, 225 cGy each day for five days a week to a total dose of 6,075 cGy. He is now in his fourth week of treatment at 4,050 cGy and experiencing side effects. His voice is a high-pitched whisper and talking requires a lot of effort. He reports pain when swallowing his favorite foods like nachos and has lost 2 kg since his last weight check four days ago. Bob also reports some dizziness with position changes, and his pulse and blood pressure screenings show that he’s mildly orthostatic.

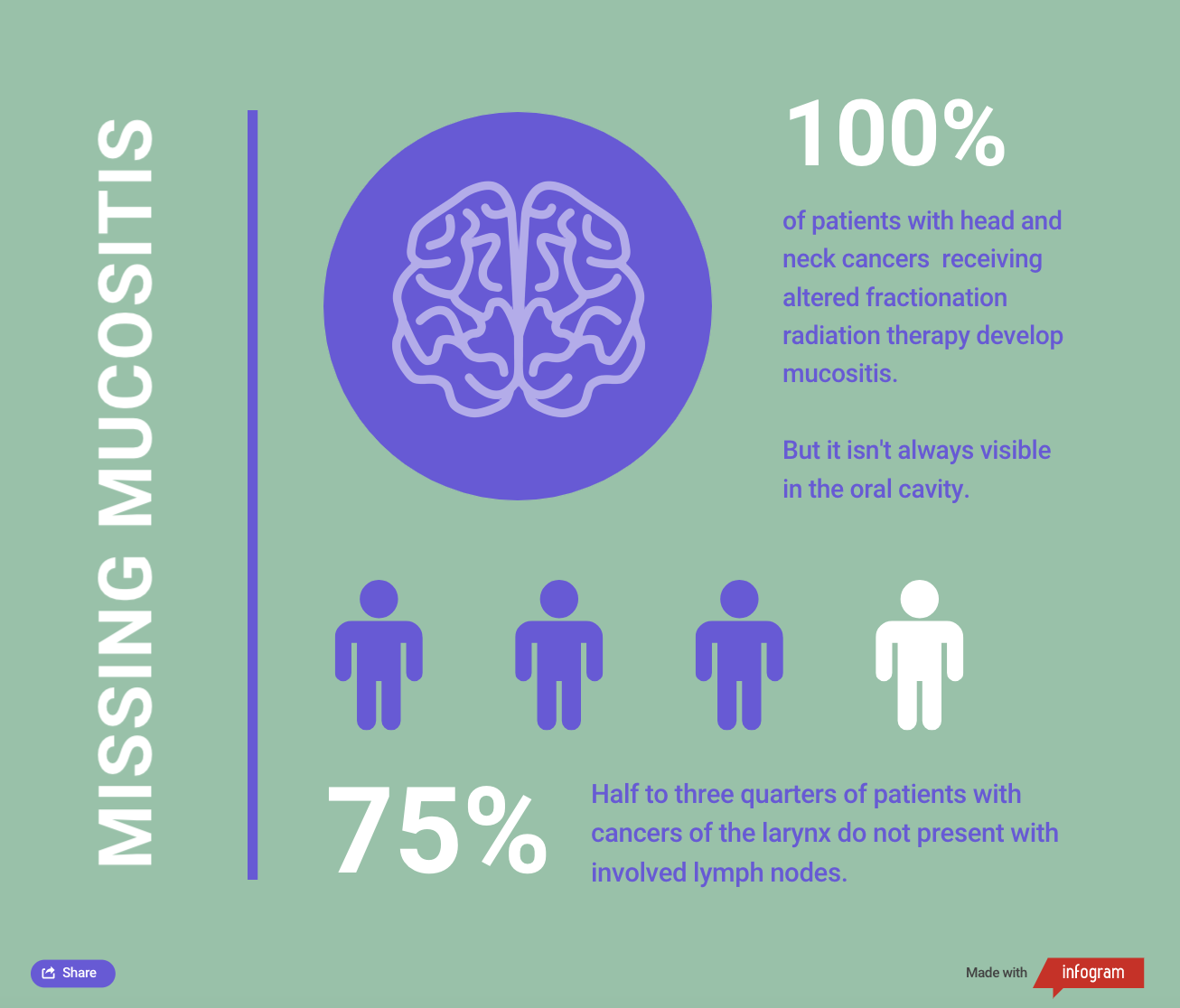

Bob was excited that he made it through the first few weeks with no pain medications and had hoped he could get through the rest of treatment without any. He told his care team that he cut back on drinking and smoking “a lot.” As Bob’s nurse, you did your research and found that oral mucositis can present in up to 100% of patients with altered fractionation head and neck cancer (HNC). You ask Bob to open his mouth so you can examine it, but you see no erythema, ulcers, or mucositis. Bob’s mouth looks healthy, moist, and intact.

What Would You Do?

HNC is a group of diseases in an anatomic area with multiple organ systems, including the lips and oral cavity, nasopharynx, oropharynx, larynx (where the glottis is located), hypopharynx, salivary glands, and paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity. Each area has different risk factors, functional losses, and treatment-related side effects.

Cancers of the larynx are heavily associated with excessive alcohol and tobacco use and are predominantly found in male patients. If Bob does not stop smoking or drinking, the chance of his cancer being cured decreases and his likelihood of developing new cancers increases.

Note: Based on information from Elting et al. and National Cancer Institute.

Highly conformal radiation therapy treatments have become much more precise, which has limited radiation-induced mucositis to the dose distribution and target volume. In practice, this means that it typically appears only on the body area being treated. A patient receiving radiation therapy to the vocal cords might not receive significant radiation dose to the oral cavity, so they shouldn’t have extensive oral toxicities. Half to three-quarters of patients with laryngeal cancer do not present with involved lymph nodes, which allows the radiation oncologist to effectively treat a smaller field with a higher cure rate. However, radiation side effects are cumulative, so Bob’s discomfort will likely grow as he receives more radiation therapy.

The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events 5.0 now separates oral mucositis from laryngeal mucositis. When you assess Bob’s mouth for mucositis, you’re only able to see the oral cavity and a part of the oropharynx. The other structures are not visible, which may incorrectly grade Bob’s mucositis as 0. You’re aware that Bob will have mucositis with his treatment regimen, but because it clearly isn’t oral mucositis, you meet with the radiation oncologist, who decides to conduct a nasopharyngolaryngoscopy. Based on the findings from the procedure, the radiation oncologist diagnoses grade 2 laryngeal mucositis.

As his nurse, you encourage Bob to focus on foods that are mechanically soft or liquid. You also ask him to avoid alcohol and spicy, scratchy, or acidic foods and refer him to a dietician for nutritional support. The radiation oncologist prescribes pain medications because topical analgesics can’t be applied to laryngeal mucositis. With proper diet alterations and analgesia, Bob feels better and is able to comfortably adhere to his radiation therapy protocol.

Editor’s note: The author thanks Scott Floyd, MD, PhD, for his assistance with the article.