By Anne Richter, MSN, RN, AGCNS-BC, OCN®, and Anne Snively, MBA, CAE

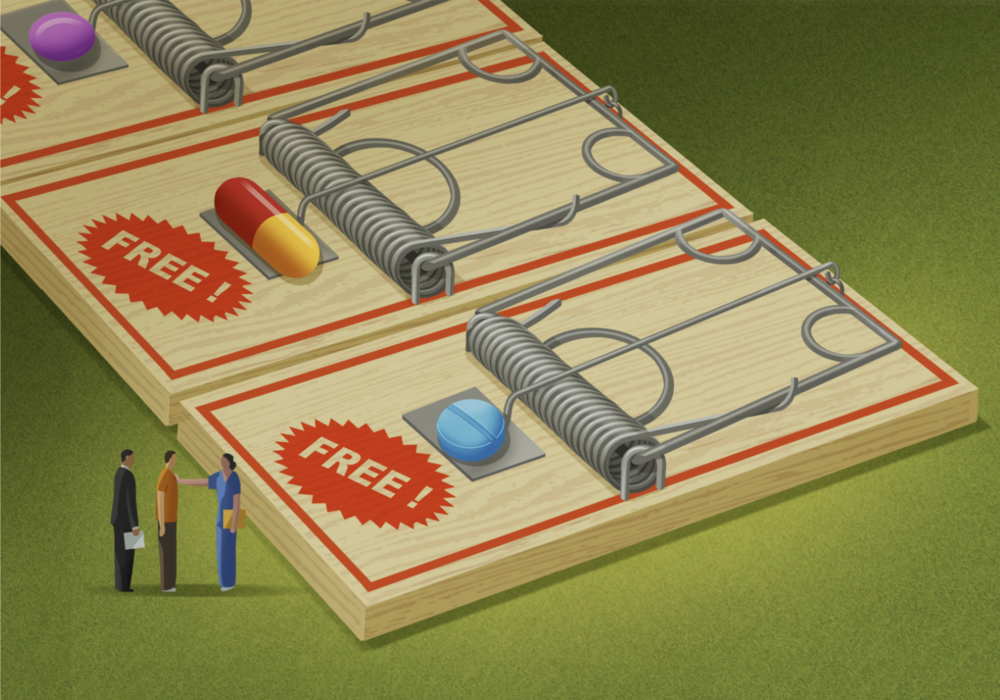

If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. Many employers are beginning to learn that lesson about alternative funding programs (AFPs), but patients are the ones bearing the brunt of the burden. Oncology nurses have a responsibility to understand that lesson, too—and the power to promote awareness and change.

In the United States, people have several ways to access prescription drugs, including government-funded healthcare programs (Medicaid or Medicare), employer-sponsored healthcare plans (commercial health insurance), or self-insurance. Healthcare coverage is typically paired with pharmacy benefits to cover the cost of many prescription medications.

Among the rising number of oral drugs used to treat cancer, many are categorized as “specialty drugs” and are very costly for a variety of reasons, mostly because of the intricate research, development, and manufacturing processes required to create them. About 2% of the population uses specialty medications, but they represent about 51% of the costs of prescription drugs. The average cost of a specialty drug is $38,000 per year, compared to $492 for a nonspecialty drug.

When the drugs are not covered in whole or in part by a health plan, patients may face a financial burden to pay for them, receive an alternate IV treatment, or forced to forego the necessary treatment because they cannot afford it, thus worsening their outcomes. Employers can also experience financial strain in covering the drugs for their employees.

A Solution That Leads to More Problems

AFPs are run by third-party, for-profit vendors that target self-funded plans. They claim to help companies reduce their healthcare costs by offloading the plan’s responsibility for covering most or all specialty drugs. AFP vendors do this by carving out (excluding) or automatically denying prior authorization for specialty medications and then promising to help patients or healthcare providers access the medications or services from patient assistance programs (PAPs). Patients are required to work with the AFP vendor or be left paying 100% of the cost of their specialty medication.

A 2022 study found that 10% of employers with at least 5,000 employees were using AFPs and another 27% were considering them. The plans are appealing to employers because of the continually rising costs of health care and efforts to attract and retain quality employees.

Ashley Sumrall, MD, FACP, FASCO, the Association for Clinical Oncology’s alternate delegate to the American Medical Association, said she’s witnessed the harms of those programs first-hand. She has had patients start oral chemotherapy regimens covered under AFPs, then “abruptly lose that coverage, and, as a result, lose their access to treatment for unclear reasons. Given the importance of timely access to cancer care, it is stressful for patients and unsettling for clinicians to have access to chemotherapy revoked this way,” Sumrall said.

“For more sophisticated practices that employ full-time financial navigators, AFP vendors come between the patient and the practice, throwing up unnecessary roadblocks and delays. These practices routinely work directly with patients on obtaining financial assistance where necessary, and the AFP vendor simply adds another unnecessary layer to an already stressful process,” Sumrall said.

In the Battle for Dollars, AFPs Win Every Time

Amy Niles, chief advocacy and engagement officer at the Patient Access Network (PAN) Foundation, is dedicated to helping people with serious illnesses access and afford treatment. She explained that vendors market AFPs as a “win-win” for the employer and the plan participant, claiming the plan saves money and the individual gets their specialty medications for little to no cost.

However, PAPs are safety-net programs that provide free drugs to truly uninsured and underinsured individuals. The AFP vendors require patients to provide proof of income and a limited power of attorney to enable the AFP vendor to act on their behalf and apply for manufacturer PAPs.

Here’s what happens next:

- The individual’s application for a PAP may be denied because of a high income. In this case, the employer could, but is not required to, override the denial as a medical necessity or approve the previously denied prior authorization.

- The AFP could attempt to seek financial assistance from a charitable foundation on behalf of an applicant as an interim measure while awaiting PAP determination, thereby using patient assistance as part of their for-profit scheme. This situation can occur only when the AFP denies prior authorization, not when the specialty drug is carved out.

- If the AFP can’t get the drug covered by a PAP, the patient may end up owing the full amount.

Regardless of whether an individual’s PAP application is ultimately approved or denied, the application process itself causes delays in access to treatment. Additionally, any amount the patient has paid to access their medication may not count toward their deductible or out-of-pocket requirements.

Regardless of who—if anyone—pays for the drug, one party does get paid—and that’s the AFP vendor. One source estimates that AFP vendors retain up to 25% of the savings off full price. Kim Czubaruk, JD, associate vice president of policy for CancerCare, shared court documents indicating that AFP vendors are selling the schemes to profit themselves by charging a cost avoidance fee of 30% or more.

Patients Feel the Pain—and It’s Not From Their Cancer or Treatment

The consequences of AFPs can be dire:

- Treatment delays: Patients have an increased chance of dying when treatment is delayed. Researchers reported finding that each month of delayed cancer treatment is associated with a 10% increased chance of death.

- Insufficient PAP funds to complete treatment: The PAP funds available for the prescribed medication may provide only a partial course of treatment.

- Money being diverted from those who truly need it: AFPs take away funds intended for individuals who are uninsured or underinsured with limited or no access to medications. “They are putting charitable funds, designed to support our most vulnerable, at risk,” Niles said.

- Use of potentially harmful drugs: Many AFPs also rely on medications from overseas that may be substandard, unsafe, ineffective, or lower quantity than those prescribed.

- Influencing treatment decisions: Providers may be presented with situations in which a PAP is available for one treatment but not another.

- Increased costs: Patients may simply not qualify for assistance programs because of their high incomes. After delaying treatment trying to get the PAP coverage, they could end up paying the full amount anyway.

Niles said that AFPs present a number of ethical and legal issues that she hopes people can better understand. “If the plan is carving out these specialty medications . . . then, in essence, they’re discriminating against people who are seriously ill—so that is a problem,” she said. She described “dubious” and “questionable” business practices, such as requiring patients to sign a power of attorney or provide sensitive information.

“These are truly schemes, and it’s very difficult for patients to understand what they’re in the middle of,” Niles said.

Sumrall agreed. “By design, these programs are opaque to both patients and providers,” she said. “AFP vendors will not provide affected lists of drugs to practices and present themselves to patients as partners in their care.”

Take Action: Raise Awareness and Advocate, Advocate, Advocate

“One of the keys here is education. It is important for providers to recognize when these programs are impacting their patients and, for those practices that have the resources available, that their financial navigators are aware of these programs and the delays they can cause. The American Society of Clinical Oncology and other organizations are bringing these concerns to the attention of government regulators with the aim of increasing awareness and minimizing the negative impact on patients and practices.”

Czubaruk and Kollet Koulianos, senior payer provider consultant with the National Bleeding Disorders Foundation, have established a task force comprising representatives from more than 15 organizations dedicated to raising awareness about AFPs. The task force is educating stakeholders—including patient organizations, providers, employers, and policymakers—about AFPs’ dangers and is currently engaging with federal agencies to clarify whether or how AFPs comply with the law and for agencies to take appropriate action.

As part of that work, Czubaruk is collecting patient and provider stories explaining how AFPs affect patients’ timely access to their prescribed specialty medications. She’s using the stories to educate other patients, providers, employers, and policymakers about how AFPs manipulate self-funded plans and drain PAPs to the detriment of all individuals—whether insured, underinsured, or uninsured—who rely on specialty medications to manage or treat their serious medical conditions.

Czubaruk shared several stories she’s collected of patients who discovered their specialty drugs weren’t covered and had to use AFPs. Each experienced significant treatment delays.

In one case, a patient with a well-known insurance provider had a pharmacy program embedded in the coverage that excluded specialty medications. The patient ultimately did get approval from a PAP, but treatment was delayed for a full month. In other cases, patients didn’t qualify for assistance because of income levels, but the programs either indicated they would cover them or provided confusing or misleading statements about coverage. In two cases, the patients proceeded with treatments only to be left paying completely out of pocket. Another patient is still waiting for treatment at the time of this writing.

“AFPs entangle providers in the process, which may influence treatment decisions and outcomes,” Czubaruk said. She explained that the healthcare provider needs to be an advocate for the patient.

As primary patient advocates, here’s what Czubaruk said that nurses can do:

- Ensure you are providing clinical information and patient implications to those who are seeing approvals.

- Maintain an up-to-date list of resources and programs to share with insured, uninsured, and underinsured patients, and, to the extent possible as desired by the patient, assist them in completing forms and providing timely medical documentation if needed.

- Collect deidentified patient and provider stories; share them with patient advocacy groups, state and federal legislators, and governors; and encourage the providers you work with to do the same. There is no better agent of change than real-life stories and experiences, Czubaruk said. You can also share your stories with her for the task force project.

“Employers’ efforts to source free products from programs meant to help those without coverage turns our employer-based healthcare system on its head, jeopardizing meaningful access for millions of people with employer-sponsored plans as well as for those without coverage who depend on PAPs,” Czubaruk said. “These programs and their aftermath will result in worse health outcomes for all and exacerbate existing health disparities and inequities.”

Your Voice Has the Power to Effect Change

Ultimately, this is a critical advocacy issue for oncology nurses. As Niles said, “There’s no shortage of issues to advocate for, but this one is particularly bad. It’s inequitable.”

Sumrall agreed. “Clearly, all of this impacts equitable access to care,” she said. “We need to get the attention of policymakers that these programs are impacting patient care, diverting resources, cost the healthcare system more money overall, and need to be reined in.”

Niles and Czubaruk also urged nurses to get involved in education and advocacy. Start by making sure your own employer-provided insurance and that of your friends and family provide coverage for specialty medications. In addition, nurses can raise their voices to urge agencies and policymakers to prohibit discriminatory schemes that jeopardize patients’ access to lifesaving and life-preserving medications.