The Case of the Late Head and Neck Lymphedema

By John Hillson, RN, BSN, OCN®

Samuel, a 55-year-old patient with a history of T3N1M0 oropharyngeal HPV+ cancer on the base of his tongue, underwent surgery followed by 70 Gy of intensity-modulated radiation over seven weeks with concurrent weekly cisplatin. He responded well and had a positron emission tomography (PET) scan three months post-treatment that showed no cancer. Two months later, Samuel calls the triage line to report swelling on the left side of his neck, the same area where he first noticed a lymph node that led to his initial diagnosis.

The swelling comes and goes throughout the day, and he has difficulties swallowing and reports feeling like something is caught in his throat. Samuel also reports a stiff neck, occasionally restricted range of motion, hoarse voice, and a need to sleep with his head elevated because of difficulty breathing. He says he’s concerned that his face appears deformed. Samuel seems confused because he was initially feeling significantly better after treatment and asks the triage nurse if his cancer has returned.

What Would You Do?

Secondary lymphedema typically affects patients with breast cancer (https://www.breastcancer.org/treatment/lymphedema), but researchers have found that as many as 90% (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hed.26394) of head and neck cancer survivors experience the side effect to some degree within two to six months after therapy (https://www.oncolink.org/cancers/head-and-neck/head-and-neck-cancer-survivorship/lymphedema-after-head-and-neck-cancer).

The head and neck region contains more than 300 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513317/) lymph nodes, and when tumors or cancer treatments damage soft tissues and lymphatic structures of the head and neck, patients may accumulate high-protein fluid in interstitial tissues. As the incidence of some head and neck cancers increases (https://www.cancer.gov/types/head-and-neck/hp/adult/oropharyngeal-treatment-pdq) and survival rates improve (https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.3322/caac.21343), clinicians must watch for survivorship issues like lymphedema in this patient population. Although it’s a common late effect, head and neck lymphedema remains understudied (https://onf.ons.org/onf/38/1/lymphedema-patients-head-and-neck-cancer) and methods of diagnosis and measurement are limited (https://journals.lww.com/rehabonc/Fulltext/2021/10000/Head_and_Neck_Lymphedema_Assessment_Methods.12.aspx?WT_mc_id=HPxADx20100319xMP).

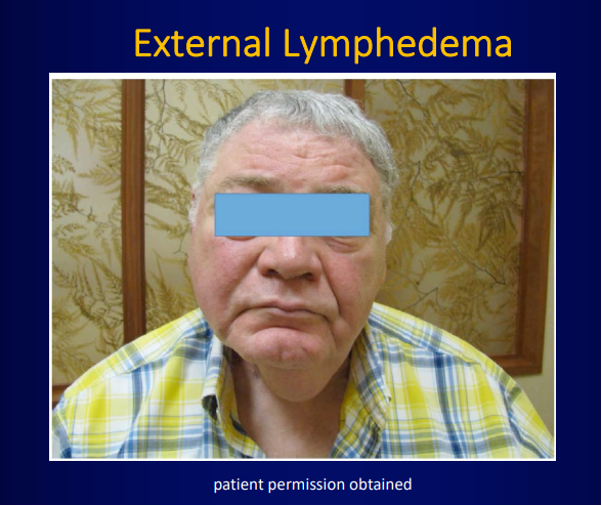

Externally, depending on the location of the surgical incision and radiation treatment field, lymphedema can be disfiguring and trigger anxiety (https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.libproxy.uncg.edu/pmc/articles/PMC4111092/pdf/nihms602986.pdf) in patients. It can also affect the neck’s musculature, leading to nerve impingement, pain, and impaired cervical and shoulder range of motion.

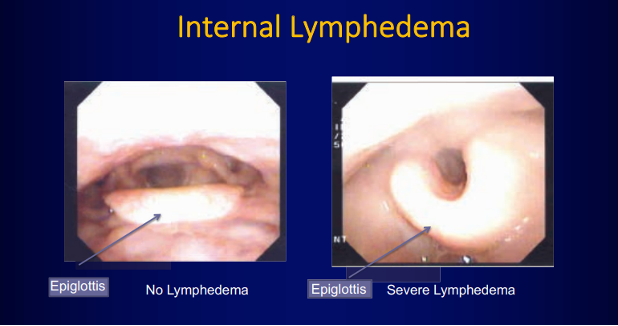

Head and neck lymphedema may develop internally (https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/jpm.2016.0018), with a wide range of symptoms depending on the treatment area. Tissue swelling in the upper aerodigestive tract can narrow or obstruct the airway. Lymphedema may impair speech, vision, and hearing and compromise essential structures for safe and effective swallowing. Although the symptoms may resolve on their own, they can also become severe (https://youtu.be/usqzHmDOMxk). Patients may have a fear of recurrence or question whether the changes are permanent and represent their new normal.

You review the literature and suspect that Samuel has lymphedema. You contact his radiation oncologist to first rule out recurrence; then you consult the ONS Guidelines™ for Cancer Treatment—Related Lymphedema (see sidebar). Because Samuel is now back at work and must wear tight shirt collars and ties, which can worsen lymphedema, after your assessment, you make refer him to speech-language therapy and a lymphedema specialist for complete decongestive therapy.

After two weeks, Samuel reports substantial improvement in his symptoms, and you and the therapists educate him about self-massage and stretching exercises (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00520-016-3356-2) to do at home. You also share some online resources (https://youtu.be/VQdLZ26r-rU) for patients with head and neck lymphedema (https://www.headandneck.org/lymphedema/).

Because you, as his oncology nurse, caught it early and intervened with the cancer care team, Samuel’s lymphedema is manageable with daily self-care.